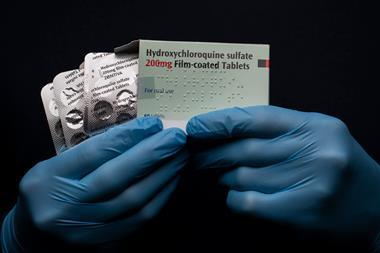

Hydroxychloroquine has had a busy few months. After being repeatedly endorsed by US President Donald Trump as a treatment for Covid-19, the decades-old cheap antimalarial drug has shown the scientific process for what it truly is: a tricky and messy one, often framed by different players to fit their own agenda.

Hopes first emerged after a small-scale observational study published in March suggested that hydroxychloroquine – now used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and lupus – might help treat Covid-19, especially when it is administered alongside the antibiotic azithromycin. But the study soon came under scrutiny, and the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (ISAC), which runs the journal that published the study, distanced itself from it, expressing reservations.

‘Concerns have been raised regarding the content, the ethical approval of the trial and the process that this paper underwent,’ ISAC and journal publisher Elsevier said in a joint statement in April, noting that the study will undergo additional peer review.

Other hydroxychloroquine studies have raised eyebrows too. Another analysis, published in The Lancet on 22 May, that suggested that the drug can cause a potentially lethal irregular heartbeat ended up being pulled. That study was retracted by three co-authors after Surgisphere – the obscure and little-known company that collected the data – declined to make trial data available for an independent audit.

‘It was a real scandal,’ recalls Nicholas White, a physician and tropical diseases researcher at Mahidol University in Salaya, Thailand and the University of Oxford, UK. What happened next derailed any chance of quickly finding out how effective hydroxychloroquine really was against Covid-19.

On hold

The World Health Organization’s Solidarity trial, which had been testing the four most promising treatments for the novel coronavirus halted testing of hydroxychloroquine, as did the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and the National Institutes of Health. Meanwhile, the US Food and Drug Administration revoked the emergency use authorisation of the drug. Several other agencies took similar measures.

Even though the hype is now over, ‘it is still an open question whether this malaria drug is doing something against Covid-19 or not’, says Peter Kremsner, who studies tropical diseases at the University of Tübingen in Germany. Kremsner and his team are currently conducting one trial in patients with mild Covid-19 and another in moderately ill hospitalised patients, each with around 100 patients. One setback currently is the lack of patients in Germany, he says.

One study published in July reported some benefits from taking hydroxychloroquine. But it has since been criticised for being prone to bias like other observational studies, instead of a randomised double-blind clinical trial, which is widely considered to be the gold standard process to determine the efficacy of a drug.

While it’s welcome news that collectively researchers have designed around 1200 trials to test possible treatments, an analysis published last week suggests that many of the trials conducted so far are too small to yield any meaningful results. That study argued that large sums of money have been wasted while focusing on too few drugs – including hydroxychloroquine.

In Recovery

As of yet, the only trial in the world that produced actionable results is the UK’s Recovery trial, White says. More than 11,000 patients in NHS hospitals were enrolled in the hydroxychloroquine trial, and no clinical benefit was found. Another arm of this trial has also yielded solid evidence that the cheap steroid dexamethasone cuts deaths in hospitalised patients on ventilators by a third, making its use commonplace in the most serious cases – at least in the UK. Another two studies, one of 821 patients and the second of 2300 people, have also found no significant benefit of treating patients with hydroxychloroquine.

Still, the drug’s role in this pandemic may not be over. White’s trial, COPCOV, which was also temporarily halted but is now back up and running, is testing the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine to prevent Covid-19 in the first place, rather than treating severely sick hospitalised patients.

The initial goal of his COPCOV trial was to recruit around 40,000 healthcare workers worldwide and get them to take the drug daily for three months. ‘We want to protect healthcare workers, particularly in low and middle income countries because if they really become ill it damages health altogether, particularly in fragile health systems,’ White says.

But the trial has just begun recruiting participants, with fewer than 100 so far. White says it has become more difficult to recruit participants to the trial due to the way the drug has been framed by the media and others.

While COPCOV restarted after the Lancet study was retracted, many other trials didn’t. There’s no other evidence of harm from taking hydroxychloroquine, White says. But instead many health agencies didn’t resume halted trials, switching their reasoning from the potential harm of the drug to suggest that it doesn’t work, which, he says, ‘is strange at best’.

‘Most things were damaged by Covid-19 but not bureaucracy,’ White adds. ‘Despite all the fine words from country leaders and governments,’ he says, ‘the process itself has been very slow.’

1 Reader's comment