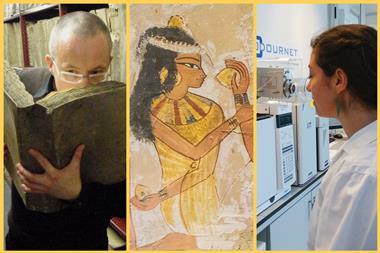

What do ancient Egyptian mummies really smell like? A team of researchers set out to determine whether their modern-day scent still reflects the embalming materials used in antiquity – and what insights it might reveal about ancient practices while also enhancing museum curation, the museum experience and conservation.

The investigation examined nine mummies from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, dating from the New Kingdom (16th–11th century BC) to the Roman period. It combined sensory analysis, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry (GC-MS-O), microbiology and historical context to develop a non-destructive method for studying ancient remains.

For the study’s sensory analysis, the team developed 13 olfactory descriptors. Conservators have long noted that mummies carry a surprisingly pleasant aroma, a claim confirmed by the study’s panel, who described their scents as mainly woody, spicy and sweet.

Analysis using GC-MS-O followed and provided a clear overview of the number of odour-active compounds. Unlike sensory analysis, which relies on human perception, this technique provided a precise breakdown of both the intensity and variety of volatile compounds, which fell into four key categories – those from ancient embalming materials, conservation treatments, synthetic pesticides and biodeterioration byproducts. However, some compounds couldn’t be identified, hinting at undiscovered sources.

In some cases, it was difficult to unequivocally categorise a volatile compound due to source overlap. For example, the aldehydes octanal and nonanal can originate from plant oils, such as orange and citrus oil, microbiological activity, lipid oxidation or degradation of human remains.

The researchers were also surprised to find synthetic pesticides, which were detectable in display areas, as no conservation reports mentioned their use. Mummies on display emitted a greater variety and higher concentration of volatiles than those in storage – likely due to the accumulation of scents inside sealed display cases.

Even more intriguingly, mummies from the Late Period (7th–4th century BC) shared distinct chemical signatures, raising the possibility that, with more data, scientists could one day identify different mummification techniques or historical periods just by their scent.

References

E Paolin et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2025, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.4c15769

No comments yet