Arbutus and Genevant say lipid nanoparticles that protect mRNA infringe six key patents

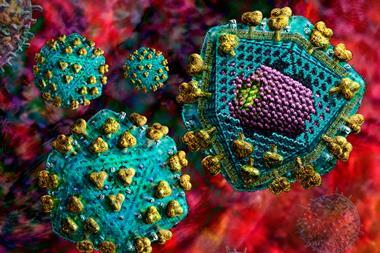

Covid-19 vaccine producer Moderna faces a patent infringement lawsuit in the US, relating to the lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that protect the mRNA in its vaccine. The suit claims Moderna is infringing technology from six US patents, developed by Arbutus Biopharma and licensed to Genevant – a joint venture between Arbutus and Roivant Sciences.

The case will not impede the sale or manufacture of Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine, but Genevant is seeking royalties for use of its patented technology.

The dispute precedes the Covid-19 pandemic. Since 2018, Moderna had sought to invalidate several of Arbutus’ key LNP patents. While one patent was invalidated in full, a second was partially upheld, and a third was upheld in full. In December 2021, a federal court rejected Moderna’s appeals against the latter two decisions, opening the door to an infringement case.

Vaccines and medicines based on nucleic acids are viewed as holding enormous potential as a disruptive therapeutic technology. ‘Historically though, these medicines have been challenging to develop,’ said Peter Lutwyche, Genevant chief executive, during a conference call with industry analysts on February 28.

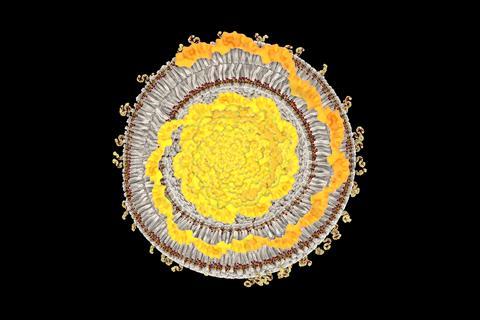

Nucleic acids are hydrophilic molecules, and do not readily cross cells’ lipid membranes. They are also easily degraded in the body, so require protection. ‘The need for a delivery technology capable of delivering RNA cargo intact to its intended target has been one of the most significant challenges in the development of these medicines,’ said Lutwyche. The answer was precise formulations of lipid nanoparticles.

Genevant says that Moderna infringed its patented recipe of four lipid types, which included cationic lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-conjugated lipids. Genevant claims that, in Moderna’s phase I trial of its Covid-19 vaccine, it used a lipid combination overlapping those covered by Genevant’s patents.

Arbutus, headquartered in Vancouver, Canada, is developing LNP technology to deliver RNA interference therapies for hepatitis B. It set up Genevant as a joint venture with Roivant Sciences to develop and license the technology more widely. Alnylam Pharmaceuticals uses it in Onpattro (patisiran). This was the first approved therapy to rely on small interfering RNA, and treats patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis – a rare, progressive, often fatal disease.

Genevant notes that it has partnership agreements in place for its LNP technologies with, amongst others, Takeda, to develop medicines for liver disease; BioNTech, for cancer targets and some rare diseases; and Gritstone, for a self-amplifying RNA Covid-19 vaccine programme.

Reasonable royalty

The penalty for patent infringement is ‘a reasonable royalty’, according to US patent law. ‘A royalty, outside litigation, in the biotech space for a typical license looks something like a single digit percent on net sales,’ says Jacob Sherkow, a biotech intellectual property expert at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, US.

When you have a big biotech product like this, there’s almost always going to be some patent disputes surrounding it

Even a small percentage of the $18 billion (£14 billion) projected 2021 sales of the Moderna vaccine will be significant, notes Sherkow. ‘I imagine the two sides are pretty far apart as to what they think an appropriate license fee is,’ he says. ‘If I was Arbutus, I would be asking for the moon. And if you’re Moderna, you don’t want to give that up. We’re going to need a bunch of interim decisions from the court before the parties can get closer.’

In a statement, Moderna said it was aware of the alleged patent infringements. ‘Moderna denies these allegations, and will vigorously defend itself against Genevant’s claims in Court. Our Covid-19 vaccine is a product of Moderna’s many years of pioneering mRNA platform research and development, including creation of our own proprietary lipid nanoparticle delivery technology.’

In 2013, Arbutus had licensed some of its LNP technology to Canadian company Acuitas Therapeutics. Acuitas later sublicensed those rights to Moderna. This sublicensing was contested in a Canadian court and settled in February 2018, ending Acuitas’ rights to use or license the technology. According to Arbutus, Acuitas’ licenses only covered four specific viral targets, not including coronaviruses.

Sherkow says the large amounts of money Moderna has made from its vaccine make patent litigation more attractive. ‘When you have a big biotech product like this, there’s almost always going to be some patent disputes surrounding it,’ he says. He suspects the litigation will take at least three years: ‘It can’t get much faster, but boy can it get slower.’

Despite the prospect of tens of millions of dollars in legal fees, Sherkow sees both sides pursuing the case through court rather than settling. ‘To be honest, for both sides it’ll be worth it,’ he says. ‘That’s just the economics of patent litigation.’ For Genevant, there is also the scientific kudos in claiming a contribution to Moderna’s highly successful Covid-19 vaccine.

Moderna is no stranger to patent disputes. The company tangled with the US National Institutes of Health, disputing claims that three government scientists had contributed to the development of its Covid-19 vaccine. In December, the company dropped its fight over the modified genetic sequence for the Sars-CoV-2 spike protein, noting in a statement that the company ‘would like to avoid any distraction to the important public private efforts ongoing to address emerging Sars-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron.’

No comments yet