Levels of nitrosamines and other carcinogens in affected tablets of valsartan and related drugs similar to smoking 20 cigarettes a day

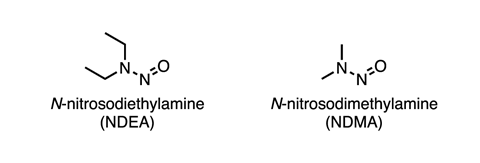

Following a spate of recalls earlier in the year, many more batches of valsartan and related blood pressure drugs are being recalled after carcinogenic impurities have been found beyond the Chinese manufacturer they had been thought to originate from. Evidence of impurities, particularly N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), has also caused withdrawals of drugs using active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from three Indian-based manufacturers.

Most recently, on 27 November Israel-headquartered Teva Pharmaceuticals recalled all of its unexpired valsartan-containing products in the US. In this case N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA) was detected in an API manufactured by Mylan India, and valsartan from India’s Hetero Labs is also affected. The European Medicines Agency has also prohibited valsartan made by Mylan India from being used in any EU medicine.

NDEA has also been found in irbesartan API from India’s Aurobindo, triggering recalls of finished drug products from US-based ScieGen Pharmaceuticals. The problem is due to process changes rather than ‘cutting corners’ according to Raghuram Pannala, head of corporate quality compliance at ScieGen. The company will now ‘be evaluating the changes proposed by API manufacturers more critically,’ he adds.

Meanwhile the US has put China’s Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical, where the problem had first been found in both valsartan and losartan, on import alert, enabling its API shipments to be detained. Contaminated valsartan from China’s Zhejiang Tianyu Pharmaceutical has also been found in Europe.

With every change in synthetic pathways there may be new compounds that need to be considered. Suppliers of APIs need to disclose their procedures

The affected drugs are all angiotensin II receptor blockers whose structures contain a tetrazole group. One established production route makes the tetrazole as a final step by reaction with azidotributyltin(IV). But in recent years, companies have published several patents moving away from that approach. ‘The idea was to avoid these chemicals that were necessary in the synthesis and that may have some remainder in the final product,’ says Maria Kristina Parr from the Free University of Berlin, Germany. ‘The idea was good but in the end it wasn’t fully thought through.’

Parr’s research1 reveals that Zheijing Huahai Pharmaceutical has patented tetrazole formation using anhydrous zinc chloride and sodium azide, preferably in dimethylformamide (DMF) solvent. The patent suggests quenching this reaction with sodium nitrite. However, under these conditions, it’s possible the DMF breaks down to produce dimethylamine, and reacts with sodium nitrite to form the NDMA by-product.

Cancer uncertainty

The resulting process has led to contamination and worldwide drug withdrawals. For example, the Central Laboratory of German Pharmacists (ZL) has randomly tested a variety of affected products, finding NDMA content of 3.7–22.0μg per affected tablet. These concentrations are relatively small, considering there would usually be hundreds of milligrams of API in each tablet. However ZL notes that people smoking 20 cigarettes a day are generally exposed to around 17–85μg of nitrosamines like NDMA.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has set up a dedicated webpage where it details an elevated cancer risk from this contamination. Based on manufacturer records, impure valsartan may have been sold for up to four years. ‘FDA scientists estimate that if 8000 people took the highest valsartan dose (320mg) from the recalled batches daily for the full four years, there may be one additional case of cancer over the lifetimes of these 8000 people,’ the webpage states.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has stated that the changes that led to this contamination first happened in 2012. The EMA also estimates that this would theoretically lead to one extra cancer case per 5000 patients taking high valsartan doses over seven years.

Danish scientists have already analysed the country’s health registries to study the cancer risk related to contaminated valsartan.2 Among 5150 valsartan users aged 40 or over who hadn’t previously had cancer, they found a 9% increase in cancer risk in those patients exposed to NDMA compared to those unexposed. However, the results had wide confidence intervals that included a potential decrease in cancer risk.

‘The results do not imply a markedly increased short term overall risk of cancer in users of valsartan contaminated with NDMA,’ the authors conclude. ‘However, uncertainty persists about single cancer outcomes, and studies with longer follow-up are needed to assess long term cancer risk.’

Pseudogeneric loophole

In a letter to the Canadian Journal of Cardiology,3 Jacinthe Leclerc from the University of Quebec in Trois-Rivieres, Canada, asks who will pay for long-term surveillance of thousands of affected patients. ‘The population needs to know, and be preventively assessed for cancer in the short and long term,’ Leclerc tells Chemistry World. ‘Causality would be very difficult to determine individually, but at a population-level, much easier.’

Leclerc also notes that the situation affects two ‘pseudogeneric’ valsartan products in Canada, supplied by Sandoz, a subsidiary of Swiss pharma giant Novartis, and Laval, Canada-based Pro Doc. Such pseudogenerics arise when drug patents expire, and patent holders sell their branded products to generic companies.

These generics are thought to be identical to the branded version, therefore not needing ‘to follow the full regular generics licensing process’, Leclerc observes. ‘The valsartan story taught otherwise: it seems pseudogenerics are not always manufactured at the same place as the brand name,’ she explains. ‘So they go unnoticed by health authorities but should have been fully tested.’ She adds that one affected Canadian manufacturer told her that NDMA was found incidentally while performing tests other than routine batch-release specification assessments.

This shows the role played by how APIs are analysed. ‘State-of-the-art API testing looks for compounds that are somewhat expectable from the synthesis that is known,’ Parr says. ‘And with every change in synthetic pathways there may be new compounds that need to be considered. Basically the suppliers of the API need to disclose their procedures.’

Chemistry World approached API producers Zheijing Huahai Pharmaceutical, Hetero Labs, Aurobindo and generic drug vendors Torrent Pharmaceuticals and Camber Pharmaceuticals to comment on the situation. They all either failed or declined to respond. The FDA declined to comment on the specifics of the chemistry involved ‘because it would involve trade secret information’.

References

1. M K Parr and J F Joseph, J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.11.010

2. A Pottegård et al, BMJ, 2018, DOI: 10.1136/bmj.k3851

3. J Leclerc, Can J Cardiol, 2018, DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.08.011

No comments yet