Troublesome side reaction becomes useful synthetic tool

Researchers from China have devised an efficient method for creating organic molecules that contain unusual, but very useful, fluorocarbon chains.1

Despite their applications in liquid-crystalline displays, chemicals featuring the tetrafluoroethylene motif (–CF2CF2–) are somewhat hard to come by. The most common industrial precursor for this motif is tetrafluoroethylene gas, which is flammable and, under certain conditions, explosive, making it difficult to transport and handle. Not only that, but the fluorocarbon chain growth process can be non-selective.

Surya Prakash, at the University of Southern California, US, was instrumental in developing tri(fluoromethyl)trimethylsilane (TMSCF3) as a trifluoromethylation reagent.2 Later known as the Ruppert–Prakash reagent, TMSCF3 is a non-toxic liquid that is widely used to endow organic molecules with a CF3 group. While trifluoromethylation has become a routine step in pharmaceutical synthesis, a safe and precise route for preparing perfluoroalkyl-bridged compounds has eluded synthetic chemists. Therefore, despite scientists recognising their potential 20 years ago, these compounds are underused.

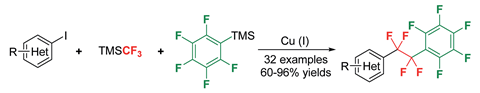

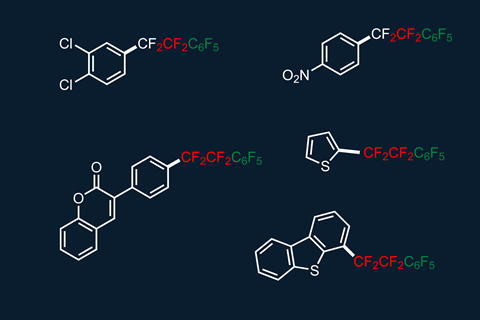

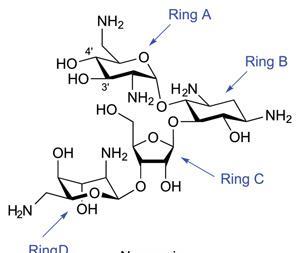

Jinbo Hu and co-workers, from the Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, have now demonstrated that the humble Ruppert–Prakash reagent is a powerful precursor for introducing perfluororalkyl bridges into organic molecules. In a previous collaboration with the Prakash group, Hu and his group had shown that TMSCF3 is a good difluorocarbene precursor and therefore a potential difluoromethylene source.3,4 Hu’s team has now taken advantage of this C1 to C2 process, by using it to grow a –CF2CF2– chain in a C6F5Cu molecule to generate C6F5CF2CF2Cu. C6F5CF2CF2Cu can then couple with a variety of heteroaryl iodides to give tetrafluoroethylene-bridged structures.

Structures with tetrafluoroethylene bridges have applications in liquid crystal displays, as the bridge between the two cyclic subunits provides the molecule with conformational flexibility. ‘What we want is to realise controllable CF2 insertion, finding an alternative way for fluorocarbon chain growth,’ says Hu. ‘In the future, we would like to insert three, four or even more CF2 moieties into certain species in a controllable fashion.’

Peer Kirsch, an expert in fluoro-organic chemistry from Merck KGaA, Germany, says that scientists had previously been frustrated if they made such structures. ‘The insertion of CF2 during copper-catalysed trifluoromethylation of iodoarenes has been known as a side reaction for decades: the resulting products always contained a few percent of the pentafluoroethyl homologue which was nearly impossible to remove from the product. It is amazing how this undesired reaction has finally turned into something useful.’

References

1 Q Xie et al, Chem. Sci., 2019, DOI: 10.1039/c9sc05018c (This article is open access.)

2 G K Surya Prakash and Andrei K Yudin, Chem. Rev., 1997, 97, 757 (DOI: 10.1021/cr9408991)

3 F Wang et al, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2011, 50, 7153 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201101691)

4 Q Xie et al, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2018, 57, 13211 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201807873)

![A picture showing the molecular structure in the solid state of [(C2F5)(F3C)2CO]2](https://d2cbg94ubxgsnp.cloudfront.net/Pictures/380x253/8/6/2/140862_Index-image-superfluorinated.jpg)

No comments yet