Straightforward skeletal editing chemistry now enables the direct insertion of nitrogen into carbon–carbon double bonds. Exploiting two different aspects of alkenes’ reactivity, researchers in Switzerland and China have independently developed ways to cleave double bonds and install nitrogen atoms in a range of simple substrates and complex bioactive molecules.

Carbon–nitrogen bonds are ubiquitous in pharmaceutical and agrochemical compounds, with an estimated 80% of new drugs containing at least one nitrogen atom. But selectively introducing this linkage, particularly into complex natural product-like frameworks, often requires a lengthy synthetic strategy. Conversely, alkenes are readily accessible: both easy to install and available as cheap feedstocks. However, methods to remove unwanted double bonds are far more limited and the harsh conditions and poor functional group tolerance of many established protocols often restrict the choice of reaction to ozonolysis or mild metathesis.

Deconstructing alkenes into nitrogen-containing functionality is therefore an extremely attractive prospect, but one that has historically presented intriguing challenges, says Indrajeet Sharma, a synthetic methods chemist at the University of Oklahoma, US. ‘[It’s] primarily due to high activation energy barriers and the need for more effective nitrogen atom donors. Finding efficient and selective methods to incorporate nitrogen into these frameworks has remained a tough nut to crack,’ he adds.

Despite these challenges, two research groups have now developed complementary strategies to convert unwanted alkenes into nitrogenous products via mild and operationally simple reactions, potentially opening up a new area of chemical space.

Reinventing the classics

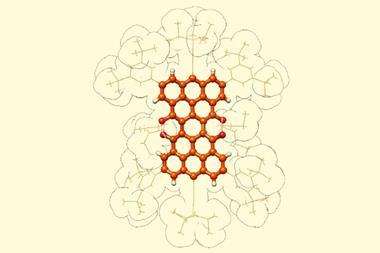

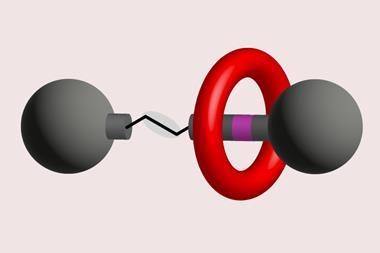

Bill Morandi and his team at ETH Zürich in Switzerland were inspired by the ozonolysis mechanism that forms carbonyl products from alkenes, via the formation and subsequent opening of a cyclic intermediate.1 The researchers have now created a nitrogen analogue of this classic reaction, which instead generates nitrile or amidine products from a variety of alkene substrates. ‘Our breakthrough came when we discovered a report by the Gassman group from 1969, which explored ring-opening reactions of aziridine derivatives using water that lead to ozonolysis like products,’ says Yannick Brägger, who worked on the project. ‘This gave us the idea that we might be able to directly create nitrogen-containing products from alkenes via aziridines.’

The team began by preparing the key aziridine ring, the nitrogen analogue of a cyclopropane. They combined hypervalent iodine with ammonia to form a reactive iodonitrene that immediately underwent a cycloaddition reaction across the double bond to form the nitrogen tricycle. This strained structure then spontaneously ring-opened into a linear allene intermediate that, depending on the structure of the starting alkene, formed either a nitrile or amidine product via a series of rearrangement and trapping steps.

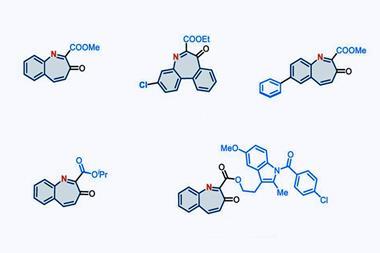

With this reactivity established, the team then investigated the generality of the reaction across a variety of feedstock and drug-like substrates. The transformation was well-tolerated, both by functionalised alkenes and drug scaffolds, including structures derived from the painkiller celecoxib and the blood pressure treatment telmisartan. ‘Molecules that contain functionalities unstable under oxidising conditions – [for example] aldehydes, thiols, or tertiary amines – are a notable limitation of our method,’ concedes Brägger. ‘But the reaction is scalable and also very robust. The setup is simple: one simply has to combine the two reagents with a cooled solution of the starting material – so we are certain that our method will find direct application in drug discovery.’

A radical strategy

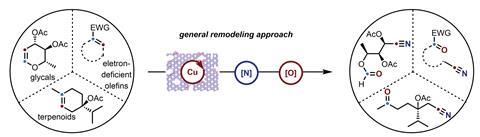

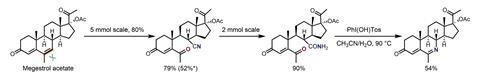

In a contrasting approach, Ning Jiao and colleagues at Peking University built upon their previous work in this area, leveraging a radical mechanism to cleave unactivated double bonds into nitrile and carbonyl groups.2 Using a recyclable copper oxide catalyst, they generated a reactive azide radical from a stable precursor, which then attacked the alkene to form a single-electron centre on the substrate. A subsequent radical reaction with atmospheric oxygen, followed by copper-mediated fragmentation, generated a single-electron oxygen species that collapsed into a carbonyl, simultaneously completing the cleavage of the alkene. Barrierless rearrangement finally formed the tethered nitrile and carbonyl product, regenerating the copper catalyst for another cycle.

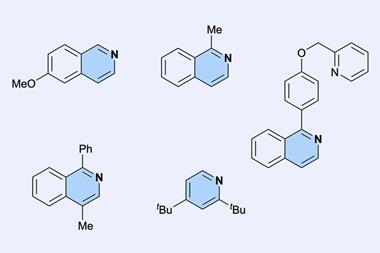

The team tested the new reaction on a range of alkenes including complex bioactive molecules like steroids, terpenoids, and glycals. In particular, demonstrations on steroidal substrates like the hormonal therapy megestrol acetate revealed the method’s potential for single-atom skeletal substitutions, with hydrolysis and Hoffman rearrangement of the cleavage products yielding the N-edited analogue.

‘Jiao’s method can accommodate a broad range of complex substrates, making it particularly effective for late-stage skeletal editing of intricate molecules,’ says Sharma. ‘A minor drawback is its occasional lack of regioselectivity with specific alkene substrates, resulting in a mixture of products, but its strengths are significant.’

Expanding possibilities

For Sharma, both approaches represent exciting additions to the skeletal editing toolbox, with the contrasting mechanisms and reaction conditions crucially offering complementary solutions to the needs of different molecular frameworks. ‘These studies showcase incredibly impressive and adaptable methodologies that can be applied to various substrates,’ he says. ‘Their innovative work opens the door to new methodologies and holds the potential to streamline synthetic routes, enhance molecular complexity, and expand the toolkit available for late-stage synthesis modifications.’

The Swiss team are already working on expanding the scope of the insertion reaction further, both to cleave other substrates such as alkynes, and to introduce alternative functionality via the key aza-allenium intermediate. Brägger is confident that the new method will bridge an important gap for synthetic and pharmaceutical chemists. ‘Traditionally, chemists make molecules by building them step by step. This breakthrough enables shortcuts to previously challenging synthetic routes which has exciting implications for synthetic strategy and drug discovery,’ he says.

References

1. Y Brägger et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adq4980

2. Z Cheng et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adq8918

No comments yet