Putting your opinions out in public, as I’ve been doing constantly for over 20 years now, is not without its risks. And I’m not referring to angry or baffled readers (although there has been a good supply of those), or to threats of lawsuits from people who feel that they’ve been wronged (there have been a few of those, too!) No, the constant risk up here on the tightrope of the printed word is that of looking like a complete fool.

It’s worth revisiting some of the topics that I’ve been more-or-less spectacularly wrong about, perhaps with an eye to reclaiming a bit of that scorched earth once it cools off. I’ll start with one that’s very much in the news these days: the GLP-1-directed obesity therapies (including Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy), Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro/Zepbound) and their successors that target related hormones). I was long of the opinion that a success like this was extremely unlikely, and I shared that view freely with anyone who asked and doubtless many who didn’t. Any ancestral creature, I would say, whose feeding behavior could be disrupted by affecting a single pathway was surely extinct: our biochemical ancestors were the other guys.

I earned that opinion by working on several related projects over the years. Every one went down in flames in the manner of all attempts at pharmacologically regulating weight without the side effects of (admittedly efficacious) drugs like the amphetamines. After years of failure from a number of directions, I felt that this might be an unsolvable problem, but I am glad to be as wrong as I am. GLP-1 therapies have been extraordinarily effective, and seem to have a number of other health benefits as well. Their story may well become more complicated over the coming years, but there’s no doubt about the results thus far.

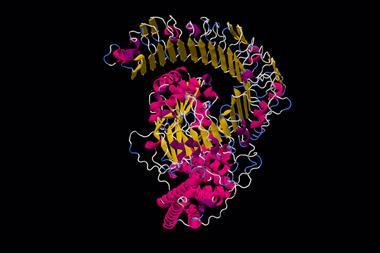

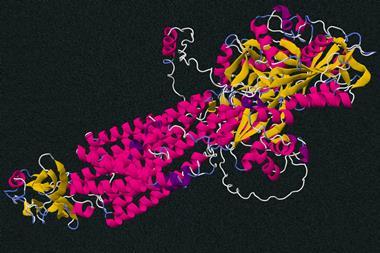

Another topic I was too pessimistic about was protein structure modeling and prediction. The extraordinary power of the current modeling systems and their rapid progress is something I never would have believed if you’d tried to convince me 10 years ago. I have a bit of a defense here, though: as I’ve said, seeing the proof back then would have convinced me in turn that we must have made extraordinary progress in understanding the physics and chemistry of proteins themselves, in topics such as hydrogen bonding, water molecule placement, entropy–enthalpy compensation, and other knotty subjects. Nope! We made extraordinary progress in computational pattern matching and mimicking how existing proteins behave, and never mind the details. If it works, it works.

Similarly, if 25 years ago you’d shown me a selection of the targeted protein degrader molecules that are currently under development, I would have been deeply confused. That was an era that was very sensitive to what were felt to be desired molecular properties, and the molecular weights of these compounds alone would have convinced me that they were hopeless long shots. Noticing that many of them included a structure akin to thalidomide would not have improved my opinion, either. I grew up reading piles of old science fiction stories, so I have a standing rule never to doubt my future self should they suddenly materialise with amazing news, but these would have been a hard sell, for sure.

Sadly, I can be wrong in the other direction as well. I would have absolutely thought at one time that we would have made more progress in Alzheimer’s disease by now than we have, just to pick one prominent example. Perhaps that’s balanced out by the ongoing advances in immuno-oncology and immunology in general (I can hope). And I can also hope that some of the fields, like Alzheimer’s, that currently look so intractable, may suddenly open up in the way that obesity therapy has, with the decades of frustration and failed trials being swept aside by something new.

But isn’t that the hope of biomedical research in general – indeed, the hope of all science? We are so often wrong about things, painfully so, before we are finally right about them. And when we eventually reach that point, we have a new platform on which to stand to start the process of being right about still more mysteries. Towards, as Francis Bacon put it so long ago, ‘the effecting of all things possible’. And I don’t think I’m wrong about that.

No comments yet