Meera Senthilingam

This week, some useful advice from Helen Scales

Helen Scales

A simple but useful piece of advice for anyone who dives or snorkels on a coral reef is to look but not touch. It’s not just for the sake of the wildlife: there are all manner of reef denizens that deliver a nasty sting if you get too close. But there is one reef dweller in particular that should be avoided at all costs.

Cone snails and are among the deadliest sea creatures, producing one of the most complex venoms on the planet. True to their name, these marine snails that belong to the genus Conus, are cone-shaped. Many are beautiful with intricate, patterned shells that can be up to 23cm long. When they’re alive and hunting, they can fire tiny darts laced with a cocktail of uniquely toxic molecules. What these slow-moving snails lack in physical prowess they more than make up for in their mastery of chemistry.

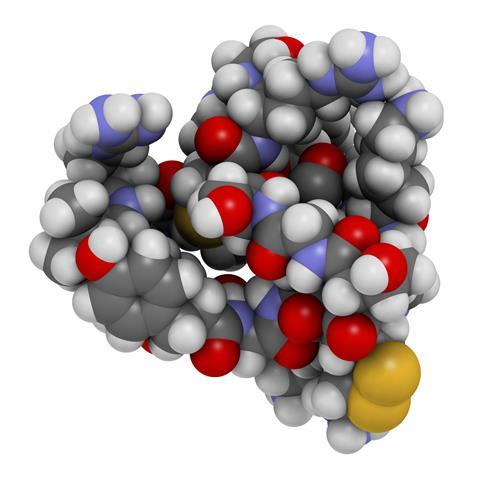

The secret to the cone snails’ deadly success is a group of peptides known as conotoxins. And there are plenty of them. It’s thought that the 5-600 cone snail species between them make as many as 100,000 different types of conotoxin; however most of them remain out there in the ocean hidden inside snails, waiting to be discovered.

Conotoxins are fairly small molecules made up of between 8 and 32 amino acids. They also tend to contain structural elements found in larger proteins including alpha helices and beta sheets. Hence they are often referred to as mini-proteins.

They work by blocking and inhibiting various parts of the nervous system; some block receptors for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine; others block calcium, potassium and sodium channels in nerves and muscles. The specific action of different conotoxins stems from their network of disulphide bonds and the presence of certain amino acids.

Loading their hollow, serrated darts with up to 100 different conotoxins at a time, cone snails instantly paralyze their prey – be it worm, fish, or another snail – before engulfing them with their stretchy stomach and settling down to digest their dinner. Humans are not on the cone snails’ menu but if disturbed or threatened they will fire away. There have been thirty known cases of fatal stings in people.

For centuries people have treasured cone snails for their beautiful shells. The glory of the sea, Conus Gloriamaris, was for a long time thought of as the world’s rarest shell. In the 18th century, one specimen was auctioned in Amsterdam for more than a Vermeer painting.

More recently, scientists have uncovered a new and perhaps surprising reason to value cone snails: their deadly conotoxins are inspiring the next generation of painkilling medicines. Because as well as blocking nerve signals to paralyse prey, conotoxins also block nerves that transmit pain: cone snails numb their victims before eating them.

Ziconotide, or Prialt, is a painkiller derived from the magician’s cone snail (Conus magus). It’s highly effective in treating chronic pain: it’s at least 100 times more potent than morphine, working in very low doses and without the risk of addiction.

But there is a drawback: Prialt needs to be injected directly into the spinal cord via a small pump worn by the patient. The problem with making a conotoxin-inspired painkiller in tablet form is making the peptides stable enough so they don’t break down in the stomach before reaching their target.

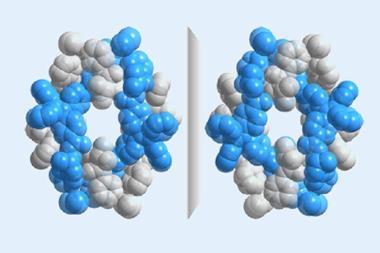

Recently, David Craik and his team from the University of Queensland in Australia think they’ve cracked the problem by engineering a synthetic conotoxin molecule and adding some extra amino acids. This transforms the peptide into a ring making it more stable. This latest oral painkiller has been shown to be effective in lab rats. The next step will be clinical trials.

Other pharmaceutical treasures could lie inside cone snails. Conotoxins have already shown potential in treating Parkinson’s disease, strokes and epilepsy. However, many of these future cures could disappear before they’re found. Most cone snails live in coral reefs and mangrove forests, two of the most threatened habitats on the planet due to climate change, overfishing and coastal development. The extraordinary cone snails are just one group of animals that would be an immense loss if they were to fade away.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Helen Scales there, with the fatal chemistry of conotoxin. Next week, a compound used, rather than feared, by humans.

Simon Cotton

Phenacetin went out of use in the 1960s, when testing suggested that it could be linked with cancers, especially kidney cancer. When phenacetin fell from favour, paracetamol – yet another aniline derived drug - was the ideal substitute.

Meera Senthilingam

Simon Cotton explains why in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet